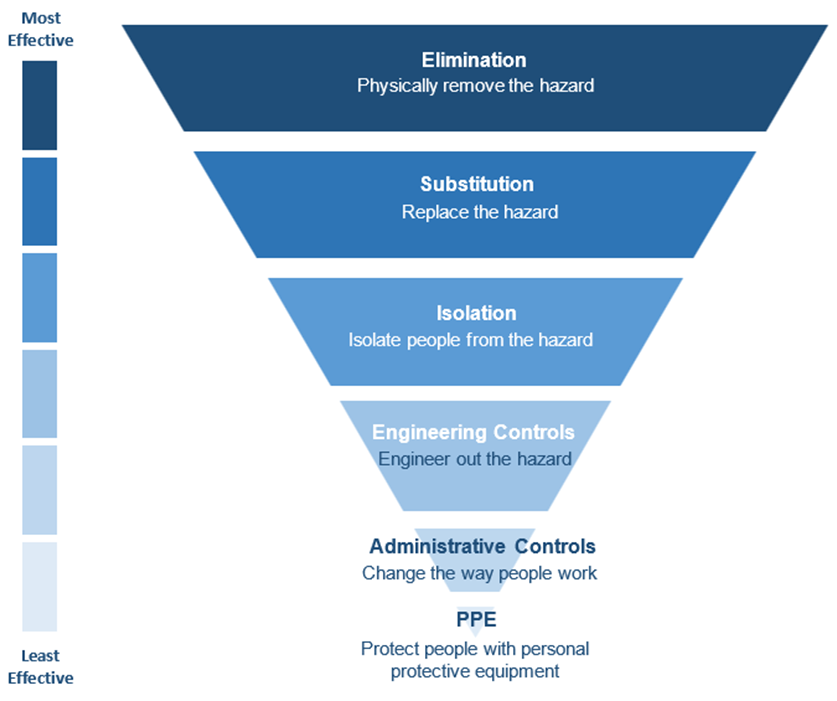

GENERAL RISK REDUCTION STRATEGIES IN INLAND WATERWAYS

The following gives a general description of potential risk reduction strategies and control measures which can contribute to drowning prevention but may not be applicable to all situations or inland waterways.

Risk reduction strategies should only be considered following a risk assessment of the relevant inland waterway and its uses. This avoids implementation of ineffective control measures which may provide a false sense of security and may inflict adverse impacts to the environment and those using inland waterways.

The risk reduction strategies are general in nature and provided to inform risk management. For some activities, locations and waterways, specific guidance is contained later in these Guidelines. They are categorised using the hierarchy of control.

Elimination

Elimination of access to a waterway may be the best risk reduction strategy. However, the intent of these Guidelines is risk management, not risk elimination or aversion. Aquatic recreation is an integral part of a healthy and enjoyable Australian life. These Guidelines are intended to support safe recreation and use of waterways.

Dredging, clearing, dragging

There are many hazards associated with inland waterways that may be transitory. Submerged objects such as logs, or vegetation and debris may be carried into an area one day and away another by the prevailing currents. A regular program for checking and removing transitory hazards should be implemented, particularly if an inland waterway is a recognised swimming location.

Figure 36: Dredging an inland waterway

Once a transitory hazard such as an animal, a submerged log or a build-up of silt or mud has been removed, there remains the potential that other similar hazards will return. Monitoring may need to be complemented by effective, instream barriers that can be effectivelydeployed and easily removed. Additional consistent control measures must be taken to warn inland waterway users of the hazard (e.g. safety signage, patrolling or public education measures). For animals such as bull sharks and crocodiles it may be necessary to implement a monitoring and management program specifically for the animal hazards to ensure safety among visitors.

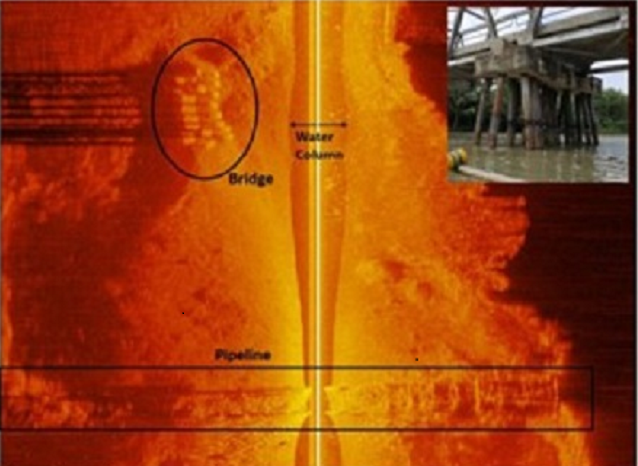

Scanning/S.O.N.A.R

SONAR and fish scanning devices can provide accurate assessments of debris, snags, rocks and other objects under water. This method of mapping waterway floor beds, particularly where recreational activities and/or swimming activities occur, is useful for identifying areas of higher risk and/or giving consideration to the removal of hazards from recreational areas.

Figure 37: SONAR imaging

Isolation

Isolation is recognised as an effective method of reducing the risk of drowning. This strategy can be implemented around dams, ponds, lagoons, billabongs and other waterways, or around features adjacent to waterways where children frequent, such as playgrounds.

Installation of barriers

Barriers can be implemented to reduce the likelihood of unintentional entry into water, where the consequence may be significant or where exposure to the water by young children is likely.

Barriers may be temporary (e.g. during an event) or permanent. Barriers can be man-made or vegetation which discourage and/or reduce access.

Playgrounds

Playgrounds are attractive for children, and there are several examples of children wandering from playgrounds to waterways and drowning. Where playgrounds are within 30 metres of the water, they should be isolated by appropriate pool fencing.

Figure 38: Barriers

Engineering Controls

Design of fishways entries and exits

Design of fishways should be undertaken in such a way as to minimise the risk of aquatic related injury and/or death to inland waterway users.

The Guidelines for the design, approval and construction of fishways (O’Connor, Stuart & Jones, 2017) recommend fishway ‘trash racks’ should be installed to "avoid debris build-up’"and recommend a 45-52 degree slope to "allow debris to rise to the surface, and constitute three times the area of the fishway channel to maximise the surface area filtered." They note "floating booms can also be installed to defect debris".

Figure 42: Fishway trash racks

More research is needed into the drowning risk presented by this design, however, additional consideration should be:

- Whether there is an entrapment risk presented by the distance between slots

- Ensuring slots are vertically arranged and not horizontally

- Ensuring a sufficiently shallow angle that a person could pull themselves to safety

- Ensuring some form of railing or exit is available in the event a person becomes trapped

- Balancing the environmental and ecological considerations with the recreational use of the area – consider zoning areas so that swimming is prohibited if necessary or designing the fishway so as not to present a risk to swimmers.

Design of specific water entry/access

Implemented to reduce the risk of unintentional entry into the water and/or used to assist in designating locations where swimming and recreational activity can take place.

Design of specific entry/access points assists in injury minimisation. Ramps, steps and ladders should be designed with the principles of equal access for all.

Figure 40: Jetty constructed for water access

Egress from waterway

Various structures have been implemented to aid with the egress of persons on vertical platforms that are difficult to access from the water.

Typically designed using ladders, ropes or chains. This does not change the hazard or likelihood of entry; however, it may increase the chance of survival by having both a means to hold on to and exit the water.

Figure 41: Egress support for waterway

Redesign gradient of water’s edge

Good design of a waterways edge or bank can reduce risks associated with entry to the water (intentionally and unintentionally) and improve a users ability to exit the water.

Figure 39: Waterfront gradient reduction Works

Safe design of pathways, trails, bridges around waterfront

Pathways should be designed at a safe distance from the water's edge, above tidal and flood levels and with sufficient ambient lighting so that they can help shape an individual’s travel path and discourage egress along the water’s edge.

A safe distance from the water’s edge will depend on a variety of factors including the nature of the landscape, waterway, activities and users. In general, pathways are recommended to be a minimum distance of 1m from the water’s edge, with 3m being an optimal distance.

Quality pathways are level in nature with no slip or trip hazards. They are built with a demarcation of the edge of the pathway and/or a barrier. These pathways are only preferred when pathways cannot be a distance from the water’s edge.

Figure 43: Safe pathway around and over waterway

Figure 44: Safe walkway adjacent and over waterway

Figure 45: Walkway over waterway

Administrative Controls

Activity plans

When conducting any organised activity in, on or around an inland waterway, the organisers should develop an activity plan. This plan should include things like start and finish times, what the activity is, where the activity is being held, equipment orders, and supervision. Activity plans may also include an emergency action plan.

A copy of the activity plan should be distributed to all participants and if appropriate, to an emergency service organisation or agency. These measures should be implemented so if anything goes wrong and the activity plan is not met, people will know very quickly (even with no communication) and be able to get help quickly.

For any large-scale event the promoter or responsible authority should require a job (or task) safety analysis and risk assessment as the basis for identifying risk in the proposed activity and the risk reduction strategies required to render the activity acceptably safe. It is common for these processes to be a requirement imposed on the responsible parties setting up and managing the event (such as contractors, security, catering, fire protection and emergency planning).

Activity restrictions/prohibitions

In addition to zoning/activity considerations, the separation of swimming and boating areas may necessitate the need for prohibition and/or warning signage advising that swimming is not advised.

If certain activities have been identified as having an unacceptable risk level, then these activities can be prohibited. Some examples of this are the prohibition of diving because of shallow water, or the prohibition of swimming while allowing boating.

For prohibitions to be effective, they must be:

- Clearly communicated and disseminated to the people who are expected to abide by the prohibitions. Signage is a good option to address this need.

- Actively enforced. A prohibition that is not enforced runs the risk of not being taken seriously by the focus population.

A distinction between the two types of signage (prohibition and warning) should be made as considerations arise with each alternative.

Fundamentally, a prohibition ‘No Swimming Sign’ can be interpreted as requiring a systemic approach of reinforcement/policing (e.g. enforceable within local laws regulations).

If it cannot be feasibly enforced, consideration should be given to erecting an advisory warning sign of ‘Swimming Not Advised’.

Consultation should be made with landowners/operators and the local laws or relevant regulatory enforcement body.

Checking the conditions

By simply checking the prevailing conditions before activity commencement, many instances of drowning and injury at inland waterways can be prevented. The following conditions should be checked prior to interaction with an inland waterway:

- Overall weather forecast

- Direction and strength of wind

- Rain forecast at the water body

- Rain forecast in the catchment area of the water body

- UV level rating

- Air quality

- Depth of the water

- Presence of submerged objects

- Presence of currents

- Strength of currents

- Water temperature

- Presence of animals

- Water quality

Community education

Education and awareness programs for residents and visitors (tourists) have been shown to be effective in controlling risks at inland waterways.

These programs outline known and likely hazards and should be implemented within communities who use inland waterways.

Additionally, local community groups should also be made aware of any potential hazards associated with their local waterway environment (e.g. primary school children).

Targeted communication should be delivered to culturally and linguistically diverse communities. Culturally and linguistically diverse communities can be at higher risk of misinterpreting or misunderstanding risk due to:

- Language and comprehension difficulties, including the ability to understand English warning signs

- Lower levels of swimming ability and water safety

- Different understandings of water safety, including hazard identification

Community groups may benefit from the delivery of a range of structured and/or informal education programs. These programs should revolve around the acquisition of survival skills, self-rescue skills and skills which enable individuals to rescue others in the safest manner possible.

Figure 53: Echuca Bush Nippers/Outback Life Savers – junior lifesaver education program for inland waterways

Designated swimming areas and patrolled beaches

Figure 53: Neptune Royal Life Saving Club

A lifesaver/lifeguard or lifeguard vehicle that periodically visits or checks shorelines should not be considered as providing a patrolled or lifeguarded waterfront and banks by either the management or waterway users.

Waterway users should be made aware of the location of supervised and unsupervised locations so that they can make an informed decision as to where to swim. This can be achieved through appropriate signage, advertising in local media, and public awareness through residential and accommodation promotion.

Emergency communication provision

Emergency phones placed in remote areas provide for emergency calling around inland waterway to access dispatch for emergency services.

Figure 54: Emergency Phone

Emergency planning

An emergency action plan is a vital tool in minimising the harm caused by a hazard associated with an inland waterway. When things go wrong, a carefully planned and well-practiced emergency action plan can reduce the negative consequences.

Emergency action plans can be developed by communities and/or councils for a local government area to address local risks and hazards as well as by individuals and families to reduce risk when in, on and around the water. An emergency action plan will need to be appropriately designed if it is to be implemented by a single person. It is more likely to succeed if there are at least two people.

Emergency action plans should not be limited to organised activities. They are applicable to unplanned activities as well.

The basic contents of an emergency action plan include:

- Response to a minor incident (e.g. minor first aid)

- Response to a major incident (e.g. heart attack or a drowning)

- Procedure for calling emergency services and an emergency communication plan

- Location of rescue, first aid and resuscitation equipment

For an emergency action plan to be most effective, all users and/or organisational emergency response personnel should be knowledgeable and well-practiced in its content.

Emergency warnings

Systems should be in place to warn users of inland waterways of imminent danger from flood, poor water quality, storm, scheduled and/or unscheduled water releases from dams, algal bloom or other significant and/or sudden natural hazard.

Warnings can be in the form of alarms, sirens, signage, SMS messages, radio announcements, closure/barriers and/or other public announcement measures.

Figure 46: Flood warning sign

Figure 47: Flood warning boom gate

Insurance

Insurance is a form of contract (policy) where financial risk is transferred to an insurance company for a fee (premium). As there are differences between policies, the document should be read carefully and the scope of indemnity fully understood. People, companies or community organisations who hold, host or plan organised activities on inland water bodies should have appropriate insurance for these events.

Local water safety plan

A local water safety plan should consider preventative activities, including swimming and water safety education, public awareness campaigns, hazard reduction, zoning, prohibitions, vessel accidents, pollution event, severe weather, structure collapse, structure climbing, descending emergencies, and natural disasters such as flooding.

The plan should be developed in consultation with all relevant stakeholders. This may include relevant personnel from the local government authorities and regional agencies for the State government, emergency services representatives and local safety organisations.

A local water safety plan should:

- Provide a criterion for risk assessment by relevant authorities

- Allow for identification of locations posing unacceptable risks to public safety with a specific focus on drowning prevention

- Support the allocation of resources to improve water safety within the community

- Identify priority actions informed by the likelihood and consequence of failing to address the identified risk

The plan and associated emergency action plan should be tested and periodically practiced, and the existence of the plan should be communicated with relevant stakeholders.

Maintenance

Regular maintenance in line with manufacturer’s recommendations should be undertaken on all equipment and plant associated with inland waterways, including but not limited to:

- Isolation fencing and gates

- Barrier fencing and gates

- Water entry and exit points

- Irrigation equipment such as pumps, inlets and outlets

- Safety equipment such as helmets and lifejackets

- Rescue equipment such as buoyancy aids and first aid kits

- Watercraft

- Engines

- Appropriate signage

Public education

Public education is a vital part in inland water safety. If a watering hole is no longer safe for swimming due to a blue green algal bloom, it is very important to let visitors know. Public education can include things such as newspaper adverts, information bulletins on electronic media such as the radio, television and the internet, public meetings, letter drops, school programs, community activities such as fetes and fairs etc.

Public awareness campaigns such as Royal Life Saving’s “Keep Watch” program are ideally suited water safety programs that can be disseminated to the public in many forms.

Public rescue equipment

Public rescue equipment is readily available equipment designed to be used by a layperson to assist in the event of an emergency. Research has shown that public access rescue equipment can reduce the water rescue time and that the use of any equipment is better than no use.

Public rescue equipment should be considered for all swimming locations or high-population-density inland waterways where visitors are known to recreate.

As a minimum, equipment provided for public use should be:

- Clearly positioned and located at recognised entry points to the water

- In colours of red and yellow at an optimal height for ease of access and positioned 1.2 to 1.5m from the ground

- Appropriately signed and co-located with safety signage

Equipment which supports out-of-water rescue techniques should be the preference, followed by an in-water (non-contact) rescue, and if necessary, an in-water (contact) rescue as a last resort.

The frequency of placement and locality should be based on a risk assessment which considers the waterway type and conditions, the types of activities that occur and the range of users.

Regular inspection of the equipment throughout the year is required and replacement/repair may be necessary. Whilst instances of theft/vadolism are low, evidence suggests that rescue equipment in secure housing may provide a deterrent. The housing should be secure but easy to open when required.

When considering the housing (casing) of equipment, the options of i) no housing, ii) open housing, or ii) closed housing are available. Each option needs to consider variables including visibility, access, UV protection, vandalism, maintenance, instruction display and cost.

Public rescue equipment can include:

- Throw ropes

- Reach poles

- Life buoys/angel rings

- Rescue tubes

Public rescue equipment that is intended to be used by untrained people should have clear instructions on how to use it.

Figure 53: Life Buoy/Throw Ring

All public rescue equipment should be readily accessible, that is, able to be accessed quickly in an emergency.

Resuscitation and advanced rescue equipment

People who are expected (e.g. for reasons of employment) to be able to use emergency equipment should be fully trained in the use of that equipment including any relevant formal qualifications.

Appropriate resuscitation equipment should be provided at any workplace or commercial activity on, in or around an inland waterway and staff should be trained and competent in its use.

Resuscitation equipment may include:

- An oxygen resuscitator

- Appropriate pocket/facemask

- Defibrillator

- Suction equipment (if applicable)

First aid equipment should also be provided, including:

- First aid kits

Advanced rescue equipment should be available to those trained personnel for workplace or commercial activities in, on or around inland waterways.

Advanced rescue equipment may include:

- A spinal board

- Straps

- Headblocks

- Rescue tubes and flippers/fins

- Rescue boards

- Inflatable rescue boats

- Watercraft

Separation of activity use/zoning

Separation of uses within an inland waterway, should be considered. With this strategy, designated swimming areas should be kept well clear of any boating infrastructure such as jetties and ramps and should be clearly marked by buoys (or similar).

Swimming and boating activities should be designated to specific zones or areas to prevent injuries or other collision-related issues.

Aquatic activity zones should be identifiable from land and while in/on the water using buoys and/or signage, and in larger areas may require a map of the specified zones.

Figure 48: Activity zoning

Signage

Signage is a widely accepted risk reduction strategy. For signage to be effective, it must be appropriate to the population, visible, legible and understandable to those who need to see it. The use of pictorial symbols placed at the appropriate position is also an important communication strategy, to ensure understanding across a broader scope of people, such as non-English speakers. Signage should comply with all industry and Australian Standards.

Figure 49: Signage on the Yarra River

Figure 50: Signage on a golf course

Figure 51: Signage at McKenzie Falls

Figure 52: Signage at Wagga Beach

Supervision

The supervision of aquatic environments, is often required in order to manage locational risks.

There are various types of supervision in relation to activities in, on or around inland waterways. Supervision can be defined as:

- Formal supervision by a trained professional like lifeguards.

- Formal supervision by a trained volunteer in the case of a community group or sporting club.

- Parent/guardian supervision of children.

Regardless of the type of supervision, children under six years should be within arm’s reach of a parent/guardian; and children under ten years should be within eyesight of a parent/guardian.

Figure 52: Inland waterway supervision

The following elements of the hierarchy of supervision, are vital components of effective aquatic supervision:

Visual supervision is vital in any effective supervision. Lifeguards at inland waterways are the most effective method of supervision. They provide supervision that is capable to prevent and respond to incidents. They can be mobile to manage changing environmental conditions. They can also modify their approach to factor for changes in user numbers and behaviours such as events.

Continuity of supervision refers to the importance of uninterrupted, undistracted and dedicated supervision in order to detect and respond to imminent threatst.

Proximity of supervision in the aquatic safety context can be defined as the location (waterway access points and edges, in a lifeguard tower, mobile, in-water, on vessel or vehicle etc.) of persons providing supervision to users in proximity to the waterway and/or in the water such that they can affect an intervention to minimise the risk of injury or death.

Timeliness of supervision is the provision of supervision at appropriate or opportune times where there is a reasonable likelihood, (determined by historical and real time data analysis), of people being in proximity to the waterway and requiring intervention to ensure their safety.

There are a range of waterway specific supervisory services that should be considered, as it is not “one size fits all”. They include:

- Full time comprehensive lifesaving service with appropriate levels of trained personnel, fixed and portable facilities, equipment, craft, vehicles and links to central command and emergency services

- Seasonal lifesaving service with appropriate levels of trained personnel, portable facilities, equipment, craft, vehicles and links to central command and emergency services

- Camera surveillance; however, the limitations as outlined above must be noted

As is often the case, the provision of supervision can be difficult to establish and is often not provided for some or all of the following reasons:

- The provision of a service may encourage attendance at a non-suitable location

- Difficulty locating suitable volunteers

- Deemed too cost-prohibitive and therefore not provided by the responsible management or ownership agency

Water safety training & education

Water safety education and training, including swimming and water safety lessons, is a vital tool in drowning prevention. Any education relevant to inland waterways should involve potential hazards associated with inland water bodies, how to identify them and what to do if an emergency occurs. Water safety education can include general water safety training courses such as Royal Life Saving’s Bronze Medallion, First Aid and CPR training or swimming and water safety education programs such as the Royal Life Saving Swim and Survive program.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Safety and personal protection equipment

Appropriate safety and protective equipment should be provided at any activity on, in or around an inland waterway. Different activities will require different safety equipment and some activities may not require any safety equipment. The best way to determine the required safety equipment for the activity is to either consult with experts, review the law and/or to undertake a risk assessment. All participants in the activity should be appropriately trained in the use of safety equipment. Safety equipment may also include provision of boat operators for those who require help with watercraft or boat use.

Safety equipment may include the following:

- Lanyards (connected to engine kill switches or similar)

- Lifejacket

- Flares

- Buoyancy control device (BCD)

- Propeller guards

- Knives

- Ropes

- Emergency Locator Beacons (EPERB)

Personal protection equipment may include the following:

- Sunglasses

- Sunscreen

- Wet suit

- booties

- Gloves

- Helmet